Exploring the battlefield of the mind

McMaster University Library archivist, Bridget Whittle highlights some of the rare and original wartime propaganda materials in McMaster’s extensive World War I and World War II collections and explains what made these unique artifacts such powerful weapons of war. Photo by: Sarah Janes

BY Erica Balch and Bridget Whittle

November 8, 2019

Throughout the first and second world wars, propaganda became a powerful tool of the state, considered by governments of all nations to be an essential weapon of war, every bit as critical as artillery, guns, or tanks.

Vast amounts of money and effort were spent on domestic and international campaigns designed to stir patriotism, shape public opinion, vilify or demoralize the enemy, or give hope to those living in occupied territories.

Propaganda took many forms and reinforced a range of messages, from posters persuading populations to enlist or contribute to the war effort, to publications encouraging citizens to ration food or be on the lookout for spies hiding in their midst.

“Successful propaganda hits all the right nerves,” says Bridget Whittle, an archivist in McMaster University Library’s William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections.

“People often think of propaganda as lies, and while that’s sometimes true, the most effective propaganda is really carefully crafted messaging that pulls on ordinary peoples’ emotions and exploits the beliefs and values that really matter to them,” she explains. “Propaganda was really targeted at average people going about their daily lives, so it can give us an interesting view into what they cared about at the time.”

On Saturday, November 23, Whittle will be hosting a special drop-in event that features a number of examples of rare and original wartime propaganda materials from the Library’s extensive World War I and World War II collections, which are considered among the best in Canada.

Below, Whittle gives a preview of some of these materials and explains what makes each of them so unique:

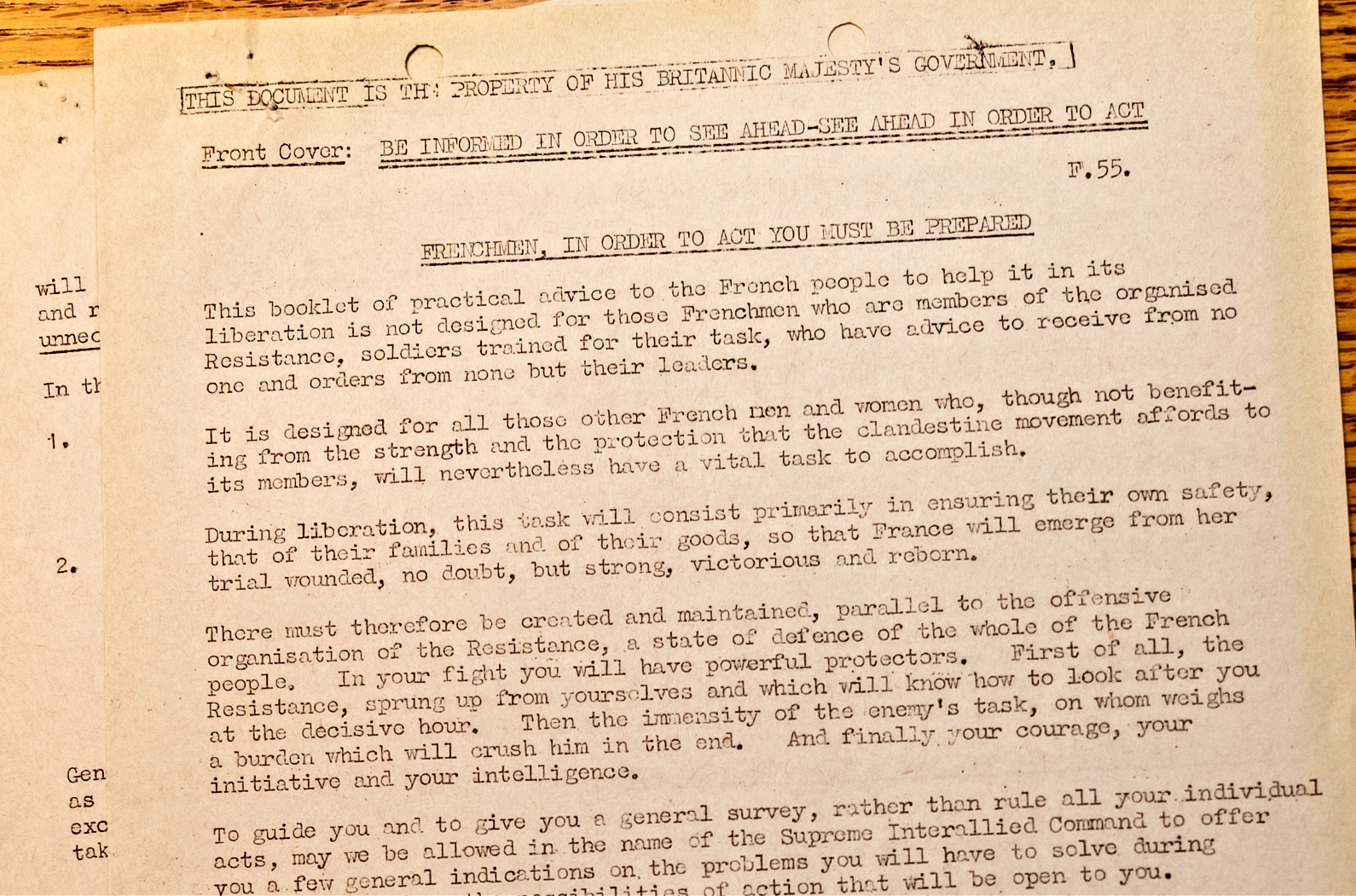

“Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?” poster, no. 79, Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, First World War poster collection

Guilt and regret have long been used as a strategy to get people to sign up. These were aimed mostly at recruiting people to fight, but it was also used as a tactic for Victory Bond sales, and numerous other campaigns.

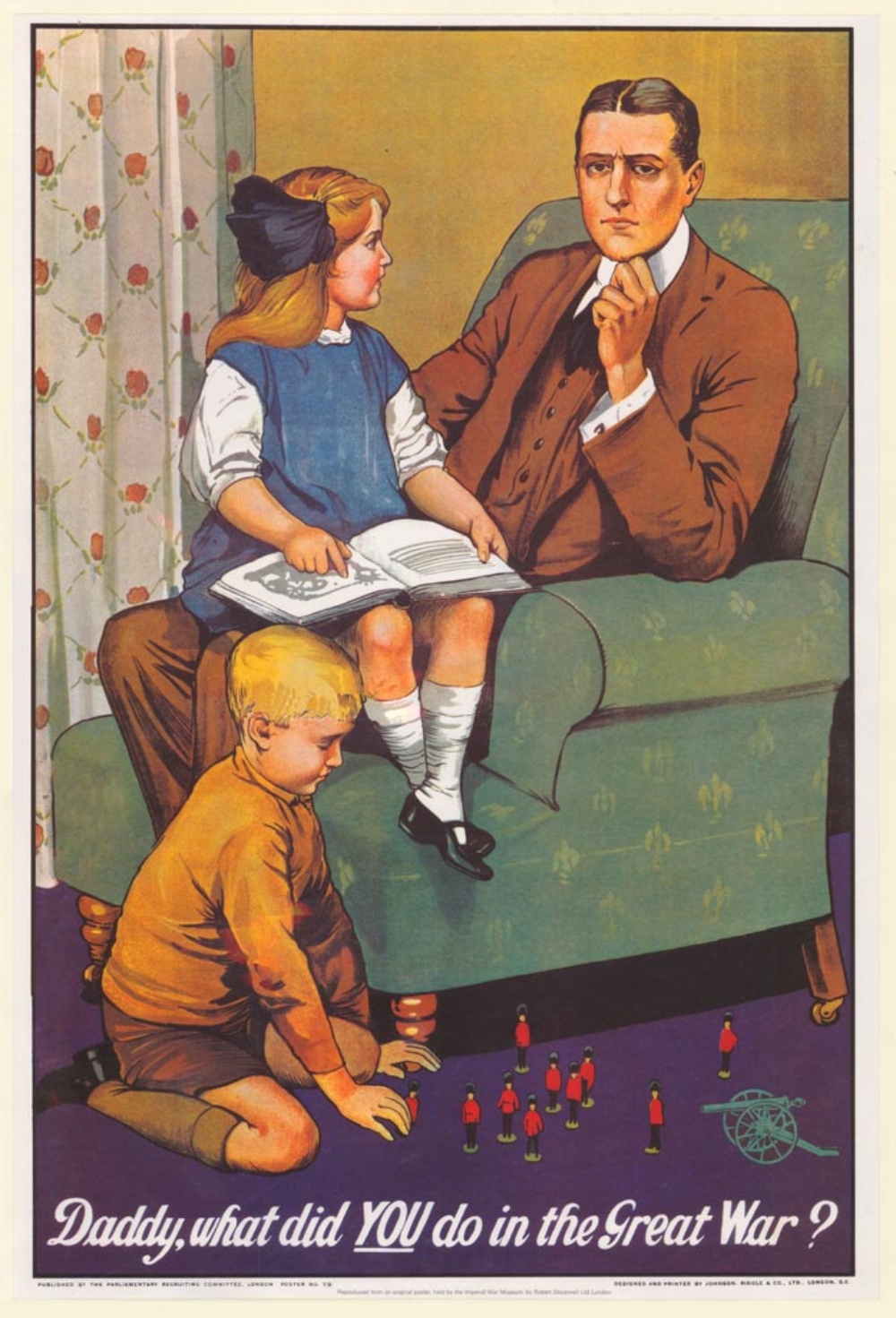

“Fish and Vegetable Meals will save wheat, meat and fats for our soldiers and allies” poster, no C25, First World War poster collection, 1914. “If the Cap Fits, Wear it!” poster, no. C3, Second World War poster collection, 1939-1945

Food, not soldiers, prompted the first national propaganda efforts in Canada during the First World War. The need to supply Canadians and their allies overseas produced national campaigns asking farmers to produce more, and regular people to eat less – especially of the three B’s – butter, bread, and bacon.

Despite this messaging, farmers in particular often felt stuck. On one hand, the government was asking them to produce more food than ever, but on the other, there was demand for the best labourers to go overseas and fight. During the Second World War, this was combated with posters such as “If the Cap Fits”, which helped to show that all contributions were necessary, whether in the field, the factory, or the front.

“To Victory” poster, no. 41, Second World War poster collection

Designed to rouse the passions of English Canadians, this poster shows Canada and Britain marching to victory together. Never has a beaver looked so ferocious.

“Victory Bonds Will Help Stop This. Kultur Vs. Humanity” poster, no.WP2, First World War poster collection

Today, people remember the sinking of the Lusitania, but during the First World War, the sinking of the Llandovery Castle was a critical rallying cry. This Canadian hospital ship was torpedoed off the coast of southern Ireland. It was against international law to attack hospital ships and in an effort to conceal the crime, the U-boat surfaced and shot those in lifeboats. It remains the deadliest naval disaster in Canadian history, with only 24 survivors and 234 dead.

“Spies Don’t Look Like This” poster, no. C36, Second World War poster collection, c.1942

Far from the war, civilians could share confidential information and easily forget who else might be listening. From troop movements and munitions manufacturing, to top secret projects (like radar components made here in Hamilton), information was a vital commodity.

External Propaganda

Propaganda was not just directed domestically, but also at the occupied countries and the forces occupying them. Much of this was done to illicit support and cooperation, but it was also aimed at demoralizing the enemy.

Occupation broadside, no., Louvain collection, First World War poster collection, 1914

The Belgian town of Louvain (now Leuven, home of Stella Artois) became a rallying cry for many of the allies during the First World War. When the city was taken by the Kaiser’s forces in August 1914, posters were put up telling civilians that they would not be harmed under the occupation. However, in response to sabotage attempts by guerillas, as well as made-up attacks, the city was burned and hostages were taken to ensure future cooperation from the occupied city.

Mechanical cards, “Dit is de Nieuwe Orde!”, no. 0034 Second World War Propaganda, 1942 (top: card cover, bottom: inside of the card)

As the war progressed, new and novel ways to entice people to look at propaganda were needed. This card was dropped on occupied Belgium, reiterating to the population that the Nazi’s would take all of their belongings.

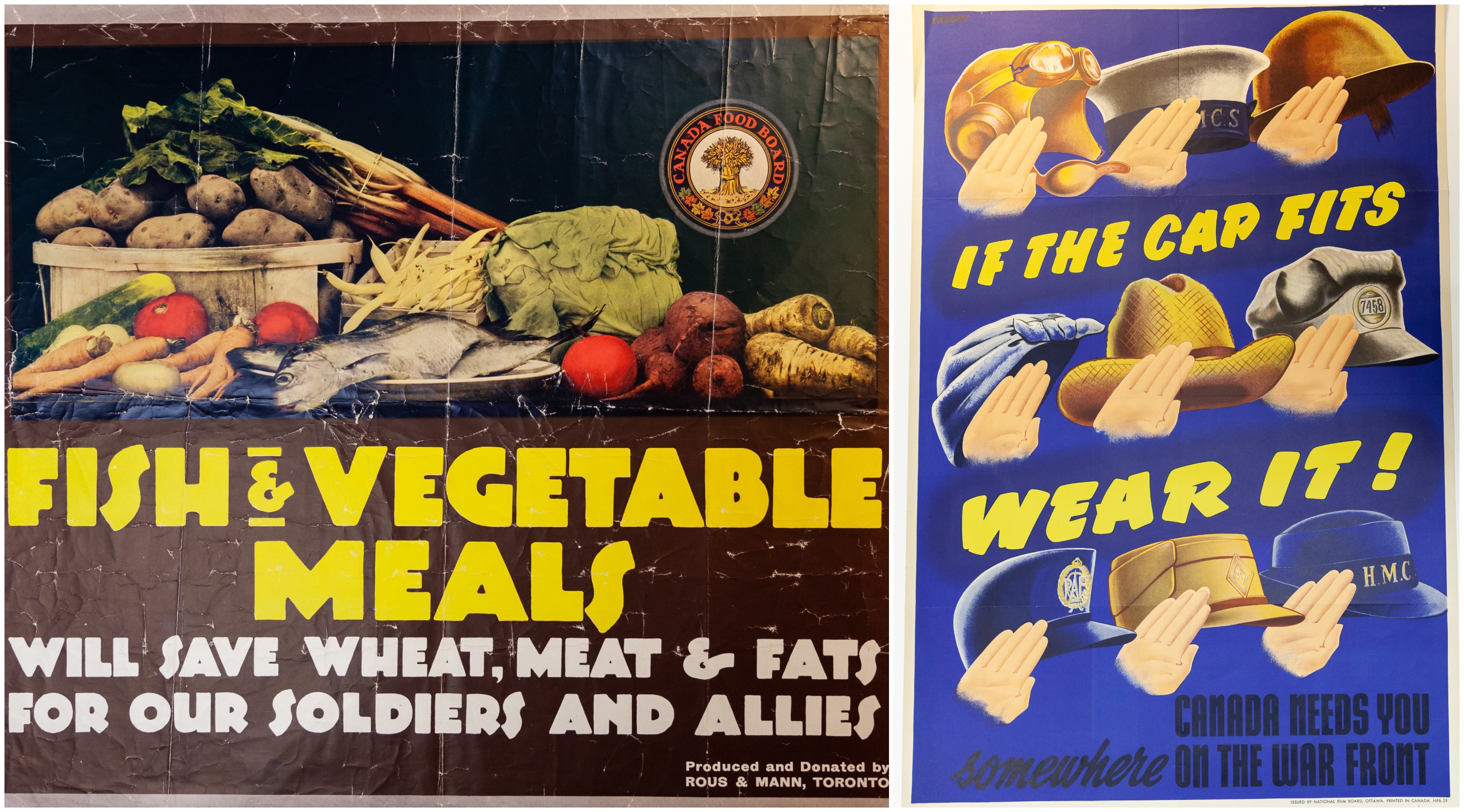

Invasion Manual, “Savoir pour Prévoir. Prévoir pour Pourvoir”, no. 0254, Second World War Propaganda Collection, May-July 1944

This set of instructions was dropped on numerous countries by the Allies ahead of D-Day, and as invasion forces pushed into Europe. They provided directions for civilians on what to do and how to behave, both to help the incoming troops and to minimize civilian casualties.

Explore these and many other examples of wartime propaganda from McMaster University Library’s collections at a special drop-in event on November 23, from 1:00 p.m. – 2:00 p.m. This event is FREE and open to the public. REGISTER NOW