History’s crystal ball: What the past can tell us about COVID-19 and our future

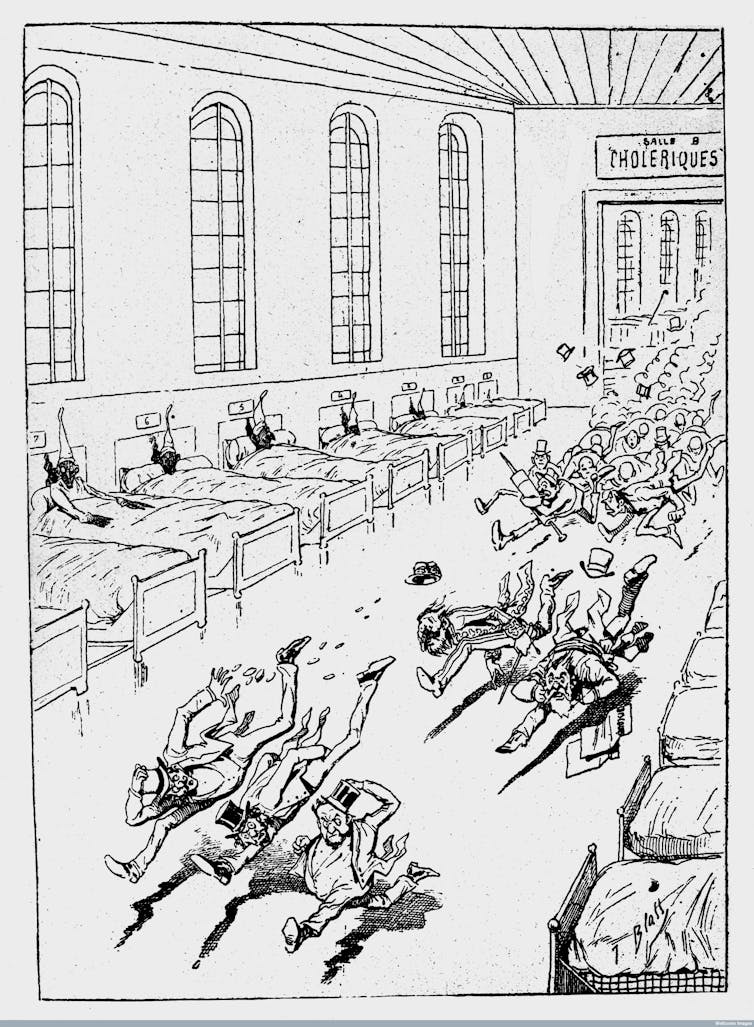

A Cholera Patient, Random Shots No. 2. Cartoon by British satirist Robert Cruikshank, circa 1832. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Library/Creative Commons

BY Ellen Amster, Hannah Chair in the History of Medicine

June 29, 2020

During this pandemic, historians have been consulted like the Oracle of Delphi. Is COVID-19 like the Black Death? The 1918 flu? What lessons of history can be applied to today?

But can history show us what we want to know?

In some ways, yes. In others, no. And we need to broaden what we ask.

As a historian of medicine, North Africa and France, I find we are using some lessons but ignoring others. Pandemic histories are useful, but how they connect with race, public health, revolution, labour, gender and colonial histories will help us explain the present and predict the future.

Lessons learned: COVID-19 responses using pandemic history

Some history lessons have been put to use right away, like social distancing.

At University of Michigan, Dr. Howard Markel compared cities in the United States during the 1918-19 flu pandemic and showed the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention how early, strict social distancing measures worked to slow infection rates. Countries around the world now use his concept, “flattening the curve.”

Not bad for the history of medicine, a field the Lancet declared “moribund” in 2014.

Lessons ignored: Poverty and racism make you sick and dead

Other pandemic lessons have been ignored, and they tragically unfold anew.

The poor, the vulnerable and workers die in greater numbers. Social reformer Dr. Rudolph Virchow wrote in 1848:

“Medical statistics will be our standard of measurement; we will weigh life for life and see where the dead lie thicker, among the workers or among the privileged.”

Poor neighbourhoods have the highest death tolls. Reformers’ maps from the 1800s demonstrated this in the United Kingdom (Edwin Chadwick, 1834) and France (Réné Villermé, 1832). The same pattern has emerged in 2020 in New York (the Bronx) and Montréal (North Montréal).

A pandemic is not the great equalizer, contrary to Madonna’s “Reflections from the Bathtub.”

Inequality of income, housing, work and opportunity are the inequities that made death “a social disease” for social reformers Chadwick, Villermé and Virchow. We now call these factors the “social determinants of health.”

That is why structural racism can be a death sentence. Data show that pandemics have disproportionately affected African Americans and Indigenous Peoples. Virchow demanded social justice as the solution: full employment, higher wages and universal education.

Policy-makers had months to protect vulnerable populations from COVID-19. Why didn’t they?

History explains that too.

Cholera: Change happens when people rise up

If history shows one thing, it’s that rich people and politicians do not want to pay for sewers, schools, hospitals, old age pensions or worker safety. The deaths of the poor themselves did not move politicians in France, Germany or Britain to big policy changes.

Like the 19th-century economist Thomas Malthus, some elites even argued that such deaths are “natural,” or in Texas recently, beneficial to society.

So how does change come?

Change came because people rose up in a series of political revolutions across Europe in 1848. Workers rose in massive strikes and revolutionary action. The fear of Marxist revolution brought health care and the welfare state to the people in Bismarck’s Germany.

And cholera pandemic also showed elites their vulnerability. If enough people are sick, if the air and water are contaminated, even rich people can die. Today you can tour the magnificent sewers of Paris and drink filtered water in Hamburg, because the rich realized they can get sick too.

Madonna was right on that one.

Health and rights are inseparable

If enough people get sick and hungry and angry, there will be revolution.

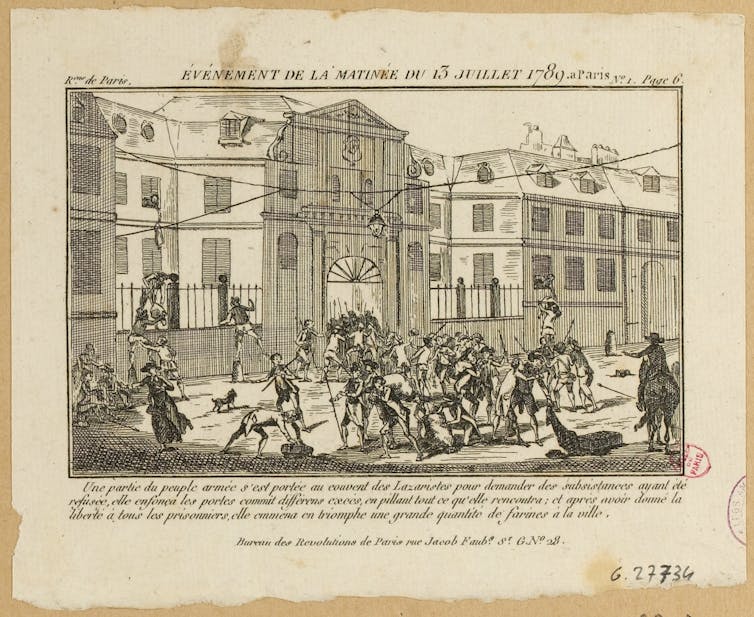

We wave flags for France on July 14, the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille in 1789 that launched the French revolution. But the day before, “bread riots” broke out and people carried food away. The combination of tyranny and physical suffering started the revolution.

Health and human rights are inseparably tied together. A government that does not allow its citizens to survive, to eat, to breathe, to live, is illegitimate. By what right does it rule? The current protests in the U.S. demanding recognition of African American lives illustrates this fundamental nature of politics.

A contemporary example of revolution to demand health and rights was the Arab Spring in 2011. A young man, Mohamed Bouazizi, lit himself on fire and his fellow citizens saw themselves in his suffering: I also cannot eat, work, have shelter or raise a family in this country. Tunisia toppled its president and wrote a new constitution.

Authoritarianism is bad for health, because public health relies on good governance.

Democracy is good for health. In 1794, French revolutionaries created the first public health system, for the “citizen-as-patient.”

Lessons from COVID-19 to global health history

COVID-19 is also teaching history new lessons.

For one, pandemics were widely considered a thing of the past.

The “developed” world expected that modern sanitation and medicine would eliminate infectious disease as a primary cause of death, known also as the “epidemiologic transition thesis.”

But “re-emerging infectious diseases” challenge this story. They are produced by modern economic and social practices.

Environmental destruction opens pathways for viruses to jump from animals to humans; COVID-19, SARS, AIDS, H1N1 and the 1918 flu are all such “zoonotic” diseases.

Modern injustices like labour exploitation, inhumane incarceration and overcrowded refugee camps directly contribute to disease spread by creating unsafe living and working conditions.

COVID-19 is helping societies rethink their histories, and how we should write history itself.

Ellen J Amster, Associate Professor, Hannah Chair in the History of Medicine, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.