Investigating the early origins of disease

BY Tina Depko, Health Sciences

January 9, 2019

Several times throughout the year, Deborah Sloboda can be found in a classroom at Dundas Central Elementary School helping to give kids hands-on learning in science.

Accompanied by those studying in her McMaster University lab, Sloboda and her team help students in Grades 4 to 8 undertake activities that range from extracting the DNA of kiwi fruit to dissecting animal organs like the lungs, heart and brain.

Photos on her lab Twitter account show her team and kids deeply immersed in the experience.

Another ? ? dissection day @ Dundas Central primary ? w @Sloboda_Lab team + @KateKennedy @CJBellissimo #Communityengagement pic.twitter.com/bYzJrL6osO

— Deborah Sloboda (@Sloboda_Lab) December 6, 2018

Kids just wanna do science ? let’s help them??? pic.twitter.com/RhgOrfpFSB

— Deborah Sloboda (@Sloboda_Lab) December 6, 2018

“Science is unbelievably cool and everyone should have the privilege to know about it,” says Sloboda, a professor in the department of biochemistry and biomedical sciences, and the Canada Research Chair in Perinatal Programming.

“We invite parents to join us for the classes, and their numbers are growing each year. This is the kind of science curriculum that can change lives.”

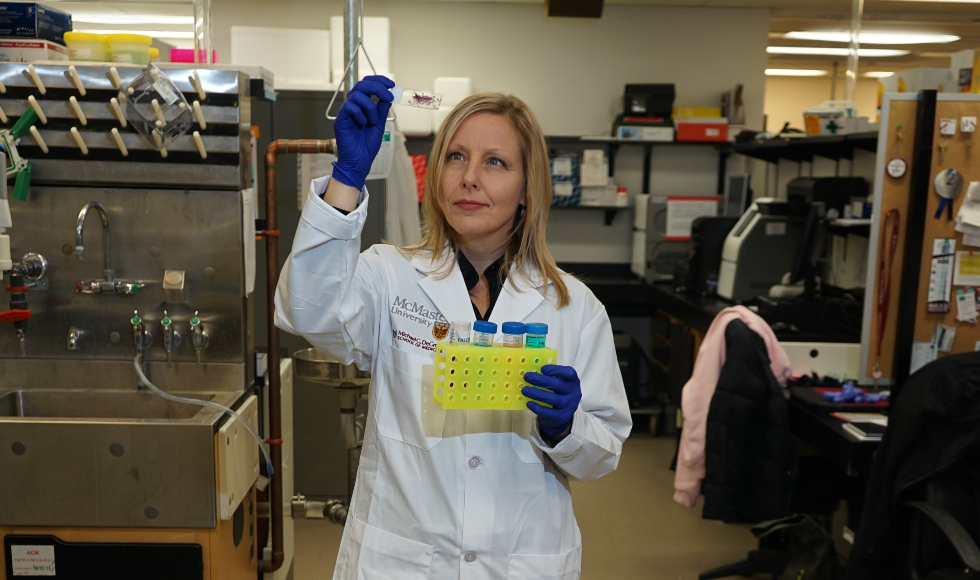

Sloboda is a fetal physiologist focused on the impact of early life environmental factors on health and disease later in life. Her field of research is called the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, known by the acronym DOHaD.

“I study how changing the early life environment impacts the developing baby’s health,” she says. “We study both the mother and the father, to understand how what they eat, and what they do, affects the baby’s development, and how those developmental changes affect the baby’s disease risk later in life.”

Sloboda’s research spans basic science in the laboratory to community public health interventions.

Among her current research initiatives are studying the bacteria, called the microbiota, in the mother’s intestine over the course of pregnancy and how it impacts the mother’s metabolism, as well as the development of the fetus and the placenta.

She also has a number of studies underway in the lab that examine the impact of the father’s physiology on sperm and the baby, with a now burgeoning theory that sperm also play a role in the development of the placenta.

Meanwhile, her Mothers to Babies Study, or M2B Study, features an interdisciplinary team with interests in developing public health interventions in Hamilton that will reduce inequities in health knowledge and nutrition-related behaviour during pregnancy.

“If I just walked around downtown Hamilton all day long and said to women, ‘Did you know that before pregnancy and during pregnancy, everything you do and eat is going to affect your grandchildren’s risk of diabetes,’ I think everyone would say, ‘Oh my gosh, why am I just hearing about this now?’ ”

Looking ahead, Sloboda is teaming up with colleague Dawn Bowdish, the Canada Research Chair in Aging and Immunity. Together, they will look at the life course of aging, which is a relatively new concept for DOHaD.

Sloboda is also working with Tracey Galloway, a researcher at the University of Toronto Mississauga who focuses on health-system improvement in northern Indigenous populations. Together, they hope to develop ways to improve pregnancy health for Indigenous women.

“We are working together to try to bring a DOHaD approach to understanding community health by working with disadvantaged populations,” Sloboda says. “It’s hard work, but I think we’re going to get there.”

Raised in St. Catharines, Ont., Sloboda was born shortly after her parents fled the Russian occupation of the former Czechoslovakia in 1968. Although both parents were university educated and math teachers in their native country, her father worked in a steel plant in Canada, and her mom took odd jobs to put Sloboda and her younger brother through school.

Sloboda attended the University of Guelph to pursue a career in education.

“I did a year in the BA program to be a French teacher, but I took a few biology courses and really loved it,” she says. “It was cell biology and learning how things worked, especially the human body, that really caught my interest. I soon transferred into human biology, but still did my electives in French. A lot of my arts courses actually helped my science courses, especially when it came to translational writing.”

It was a course in embryology during the later years of her undergraduate degree that sealed her fate.

“My fetal interest sprouted from a course examining disruptive chemicals and how they change embryo development,” he says. “I took that course and thought, ‘I have to do this for the rest of my life.’”

She earned a BSc in human biology and French at Guelph, then an MSc at the University of Western Ontario in kinesiology, with a focus on maternal exercise and its impact on metabolism during pregnancy.

After completing her PhD in physiology at the University of Toronto, Sloboda was awarded the Forrest Fetal Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Women’s and Infants’ Research Foundation, at the University of Western Australia. After five years in Australia, she joined The Liggins Institute at the University of Auckland in 2006, where she investigated the effects of maternal nutrition on maternal care and associated changes in reproductive function in offspring and grand-offspring.

She returned to Canada in 2012 after being invited by McMaster to join the Faculty of Health Sciences as an associate professor to run a research program.

“I had two children in Australia, and we knew we would eventually come back to Canada,” she says. “I wanted a job in southern Ontario, I liked new challenges and new environments, so McMaster was appealing to me. I have been tremendously fortunate in that my time here since has been fantastic.”

Sloboda says mentors have played a significant role in helping her to get to where she is today. She credits Sir Peter Gluckman at the University of Auckland for influencing her later career, and John Challis, her PhD supervisor and ongoing mentor, for helping her develop her early work.

When asked about career highlights, Sloboda points to 2015 when she received the Nick Hales Award and Challis won the David Barker Medal from the International Society for Developmental Origins of Health and Disease.

“As the two award winners that year, we had the opportunity to give lectures back-to-back, and I still get emotional just thinking about it,” she says. “That was a really big highlight of my career because I really appreciate his support.”

Challis, university professor emeritus at the University of Toronto, says Sloboda’s career trajectory is unsurprising.

“I have watched Deb grow into her career with tremendous pride and great satisfaction,” says Challis. “A good PhD student, by the time they graduate, should be challenging the supervisor and she certainly challenged me. It was clear as she went through her program that Deb had all of the characteristics that would make her a good independent investigator. She was imaginative, intuitive and had the drive that you require to achieve success in this business.”

He says her work has created change and impacted government policy and societal practices in relation to DOHaD, and will continue to do so. He adds that her challenge now is choosing how to move forward with such a variety of strengths.

“I think she will continue to develop a substantial research group,” he says. “She’s good at research, outreach and public policy, and administration, and the trick for her will be to balance those talents in each of those three different areas. She will progress in whatever area she feels her talents will be most usefully employed, but I hope she continues in all three of them as it will have great impact.”

Sloboda says that besides her mentors, the other primary reason for her success is her family, especially husband Phil Hendriks, a registered massage therapist at McMaster’s David Braley Sport Medicine and Rehabilitation Centre. The couple has two children, Simon, 17, and Ella, 14.

“I have an amazing family and an incredible partner who supports me,” she says. “Above all, without my husband’s support I would have never gotten here. There is no way I would have achieved all of this without the support at home.”

Sloboda’s family enjoys spending time together at their home in Dundas, including hiking in the area. She says they strive to eat meals together as often as possible. Unsurprisingly, the topic of conversation around the dinner table is science.

“Everything is a teachable moment in my household and we talk about science all of the time,” she says with a laugh. “When the kids were little, we used to have a whiteboard in house, and I would stop in the middle of dinner to draw things. My kids knew where the uterus and ovaries were probably long before they needed to.”

She notes her family understands her dedication to and love for both them and her research.

“Being a researcher is a lifestyle and sometimes I spend 12 hours a day here,” she says. “I think my kids realize that my career makes me a better person and a better mom because it makes me happy.”