What do lacrosse and ironworking have in common?

Associate professor (history and Indigenous studies) professor Allan Downey stands in front of a monument to ironworkers in Kahnawake, Quebec.

BY Sara Laux

September 27, 2018

For most professors, the first week back at school means meeting new students, greeting returning ones and generally getting back into the swing of things – back to work, back to classes, back to a familiar routine.

September didn’t start that way for Allan Downey, a new professor in the faculties of Humanities and Social Sciences. Rather than learning how to navigate his way around the Arts quad or figuring out the tech in the active learning classrooms in L.R. Wilson, he was in New York City, trying to decipher the subway system and finding his way around Columbia University.

Downey is spending his fall semester at Columbia as a Fulbright scholar, working with anthropology professor Audra Simpson to explore past and present articulations of Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination by researching the history of Haudenosaunee ironworkers in New York City. He’ll also be lecturing at Yale, where he’ll work with historian Ned Blackhawk, and will head to Harvard to meet up with Philip Deloria, who also specializes in Indigenous history.

The topic of Haudenosaunee ironworkers is a newish one for Downey, who is Dakelh (Nak’azdli Whut’en, Lusilyoo Clan), from a nation in the central British Columbia interior. Looking at contemporary Indigenous resurgence-based movements through the lens of history, though, certainly isn’t. His first book, The Creator’s Game: Lacrosse, Identity, and Indigenous Nationhood, which was released in paperback in August, is, on the surface, about the history of lacrosse in Indigenous communities from the 1860s to the 1990s – but it’s about much more than that.

“Here’s this Indigenous sport that’s very much a part of the epistemologies of Indigenous peoples – it’s part of their identities, part of their nationhood and part of their ceremonies,” he explains. “They introduced it to non-Indigenous Canadians, who ended up taking it, appropriating it as their own, and re-fashioning it in a way that would reflect a Canadian identity.”

Downey, who holds a PhD in history from Wilfrid Laurier University, uses lacrosse to explore the destructive consequences that accompany the creation of this largely white, Christian concept of Canadian identity, finding in it both terrible racism – lacrosse, as an example of “whiteness and Canadian civility,” was eventually used at residential schools to assimilate Indigenous youth – and hopeful developments in Indigenous self-determination, including the creation of the Iroquois Nationals, the lacrosse team that represents the Haudenosaunee Nation in international competitions.

“In doing the research for the book, working with so many elders and knowledge holders and communities, I discovered the incredible power and resilience of Indigenous people and communities,” Downey says. “This reclamation of lacrosse and acknowledging that in spite of all this colonial history, Indigenous peoples are not defined by that history – it’s not always about the Indigenous/non-Indigenous relationship.”

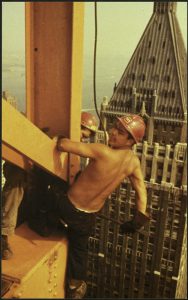

It was Downey’s research into lacrosse that eventually led to his latest project — looking at the multiple generations of Indigenous ironworkers who shaped, and continue to shape, New York City, and their role in Haudenosaunee sovereignty and self-determination.

“I kept hearing these stories about lacrosse players who were ironworkers, and I, along with co-researcher Susan Roy at the University of Waterloo, wanted to take a closer look,” he explains. “In Haudenosaunee communities like Kahnawake, just outside Montreal, Akwesasne, just outside Cornwall, Six Nations near Brantford, and Onondaga in New York state, ironworking was an industry that was open to Indigenous people when a lot of other industries weren’t – so starting in the 1920s, you have Indigenous ironworkers moving back and forth from their communities to New York City to work.”

Coinciding with a construction boom in New York City in the late 1920s, enough Haudenosaunee ironworkers moved to the city with their families to create a makeshift community in Brooklyn they called “Little Caughnawaga,” which is the anglicized version of Kahnawake. At its peak, the community numbered between 700 and 800 people – a significant fraction of the communities left behind on the other side of the border.

In fact, the community in Kahnawake is so tied to ironworking that the community – population about 8,000 – has no fewer than three monuments honouring Indigenous ironworkers.

And like lacrosse, the history of Indigenous ironworkers is inextricably linked to self-determination and sovereignty, with ironworkers from Haudenosaunee communities moving back and forth over the (imposed) international border for more than a century.

“This is a critical component of Haudenosaunee sovereignty from this territory and from Kahnawake,” says Downey. “Indigenous ironworkers are crossing the international border line and asserting their self-determination by fighting to freely cross that border and work in the United States without a Green Card, which they should have been able to do under the terms of the Jay Treaty of 1794.”

Downey’s academic work carries over to his other passion: working with Indigenous youth, translating his research into presentations and resources for communities across North America, familiarizing youth and community members with various aspects of Indigenous history and with his own personal experiences as a lacrosse player and academic.

“As a historian, I’m very much aware that Indigenous peoples and communities have been written out of history for the purpose of getting rid of us, of eliminating us, of controlling us,” he says.

“It’s important for Indigenous youth to see themselves represented in books, at the front of a classroom, in the theatre – they need to see themselves in this empowering light. Sharing my experiences with them is a way of showing them that they can pursue whatever their passion might be. Indigenous youth have so much to offer us, and we need to celebrate their positivity and resilience – and the communities and elders that have made that possible throughout the generations.”