Rare yeast pathogen causes neonatal outbreaks and is evolving quickly, resistant to cleaning chemicals: research

A stubborn and dangerous rare yeast pathogen known as Lodderomyces elongisporus is behind two outbreaks in a neonatal intensive care unit in Delhi, India.

BY Michelle Donovan

April 27, 2023

Scientists studying the stubborn and dangerous rare yeast pathogen behind two outbreaks in a neonatal intensive care unit in Delhi, India, have found that while infected patients can be treated with antifungal medications, the yeast is remarkably resistant to the strong disinfectant bleach commonly used to sanitize hospital rooms.

The pathogen, known as Lodderomyces elongisporus, typically infects immunocompromised adult patients or intravenous drug users, but has now begun to strike premature infants.

Scientists report it is evolving quickly and sexually reproducing at a much higher rate than related pathogens such as Candida auris, a drug-resistant fungus that can cause persistent and severe infections and widespread outbreaks.

The findings have been published in the journal mBio.

While an outbreak of this nature is relatively rare, invasive fungal infections in neonatal intensive care units are increasing significantly worldwide. Fungal sepsis caused by the Candida species and other fungi has become a significant cause of illness and death in already vulnerable preterm, low birth-weight babies.

In the Delhi outbreaks, clusters of infection occurred in the fall of 2021 and in early 2022. Despite repeated deep cleaning in the intensive care unit, 10 infants were infected over six months. Nine survived after being treated with antifungal medications.

“The findings are worrisome because the hospital environment seems to be selecting for stress-resistant fungal pathogens. They are adapting and evolving very, very quickly,” explains Jianping Xu, a professor in the Department of Biology at McMaster University and a lead author on the paper.

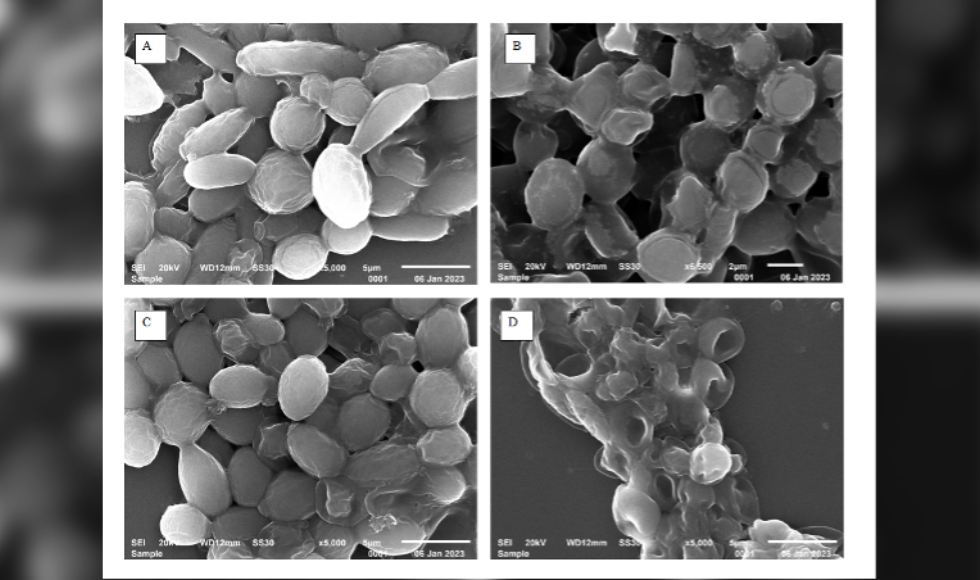

Researchers based at the University of Delhi’s V.P. Chest Institute took samples from the infants and swabbed the neonatal ICU. They found the railing and temperature-control panel of the open care warmer were contaminated with L. elongisporus.

Through genome sequencing, the team determined there were two closely related genotype clusters — one which spread from infant to infant and another found on the hospital equipment.

Further testing showed a close relationship between the hospital strains and those found in the wider world on the surface of apples. In previous research, the team had found apples treated with fungicide could be spreading drug-resistant pathogens, including L. elongisporus, suggesting fruits as a possible source of transmission.

“This yeast is among a growing list of fungi capable of causing severe infections among humans,” says Xu. “The genetic mechanisms underlying their adaptations to humans, and to hospital and natural environments warrant further investigation and measures to contain their spread and persistence.”

“If we could stop those pathogens from entering into hospital environments where many immunocompromised people are, then we’d have a much higher chance of controlling them,” says Xu.